A tiny fragment of granite and a sherd of pottery, unearthed at the tail end of an excavation in Northern Ireland, signalled the discovery of the world’s oldest excavated tide mill. Chris Catling reports back from Nendrum.

A tiny fragment of granite and a sherd of pottery, unearthed at the tail end of an excavation in Northern Ireland, signalled the discovery of the world’s oldest excavated tide mill. Chris Catling reports back from Nendrum.

Tom McErlean and a team from the Centre for Maritime Archaeology in the University of Ulster were conducting a survey of the intertidal zone of Strangford Lough for the Northern Ireland Environmental Agency, when they came across a dam enclosing a tidal pond on the shore of the Lough, close to the ruins of medieval Nendrum monastery. A short excavation in April 1999, directed by Thomas and Norman Crothers, yielded no clear evidence for the function of the pond, nor the date of the bank, until a fragment of granite millstone and a small sherd of 7th to 8th century pottery turned up in the closing hours of the dig. ‘It was one of those moments’, says Tom McErlean, ‘when a vital piece of evidence emerges that changes everything and the excitement of a major discovery takes over.’

The dig, scheduled to end in April, was extended through the summer and autumn, through the dark days of winter, until the day before Christmas Eve. By then, the eight archaeologists, who had spent the previous nine months working in the liquid mud, had secured detailed evidence and a precise date for two mills: the first dated to AD 789, and, lying beneath it, the world’s oldest known excavated tide mill, dating to AD 619-621.

The dig, scheduled to end in April, was extended through the summer and autumn, through the dark days of winter, until the day before Christmas Eve. By then, the eight archaeologists, who had spent the previous nine months working in the liquid mud, had secured detailed evidence and a precise date for two mills: the first dated to AD 789, and, lying beneath it, the world’s oldest known excavated tide mill, dating to AD 619-621.

A fish-trap perhaps?

A fish-trap perhaps?

But for those eleventh-hour discoveries, the opportunity to gain new insights into the economy of an early medieval monastery would have been lost. The triangular pond alongside Nendrum monastery, enclosed by its stony, seaweed-covered dam, would probably have been classified as a fish trap of indeterminate date — constructed to provide the monks with a supply of fish to eat on Fridays and other days of abstinence, when devout Christians symbolically remember the privations of Christ’s Passion by denying themselves the luxury of meat. This oft-quoted facet of monastic life ignores the reality of the monastic rule, as drawn up by St Benedict (c.480—c.547), founder of western monasticism, which stresses moderation in all things, including diet. Chapters 39 and 40 of the Rule specify that monks are only allowed to eat two meals a day, and that they should consist principally of bread, with a daily allowance of 1lb a day for each monk. Meat is prohibited except for the sick and the weak.

So bread, not meat or fish, featured large in the monastic diet, yet there is comparatively little evidence for its production. Water mills with a vertical wheel, a type employed since antiquity and described by ancient Greek authors such as Philo of Byzantium and Strabo, rarely survive in the archaeological record — their presence is largely deduced either from the existence of a millpond, mill race, leet or aqueduct designed to bring water to the millwheel, or from the sunken remains of a wheel housing.

‘By contrast’, says Tom, ‘salt, sea or tide mills survive relatively well, because of their watery environment. The wheelhouse of a tide mill is largely an underground structure, relatively well protected from later agents of destruction, and waterlogged for much of the time.’

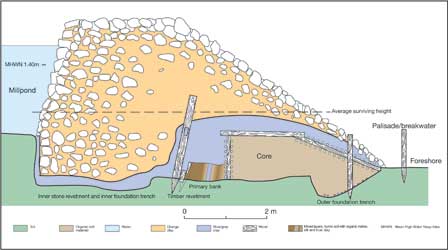

A giant water-storage tank

Tide mills depend for their power on the water stored in a millpond, which is constantly refilled by the twice-daily rise and fall of the tide. To keep that water in place at Nendrum, a long dam was constructed, about 110m in length and originally 6m wide, reaching from shore to shore to form a triangular enclosure. The dam consisted principally of an impermeable bank of orange clay, held in place on the seaward side by massive timbers, stitched internally by a framework of wattle revetments and faced on the landward side with large boulders packed with more orange clay. The floor and walls of the millpond were also made impermeable with a sealing layer of grey clay.

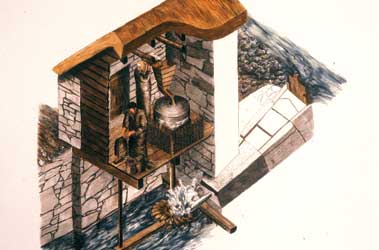

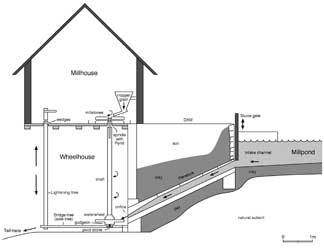

The two-storey mill building sat at the eastern end of this bank, with a wheelhouse below and a millhouse above (see box on page 31). Protruding through the bank was a narrow timber chute, called a penstock. Opening a sluice gate enabled trapped tidal water to escape from the pond down the chute, from which it emerged at high pressure to hit the paddles of a horizontal water wheel. This was connected to a vertical shaft that turned a millstone on the floor above.

The two-storey mill building sat at the eastern end of this bank, with a wheelhouse below and a millhouse above (see box on page 31). Protruding through the bank was a narrow timber chute, called a penstock. Opening a sluice gate enabled trapped tidal water to escape from the pond down the chute, from which it emerged at high pressure to hit the paddles of a horizontal water wheel. This was connected to a vertical shaft that turned a millstone on the floor above.

Dendrochronology has dated the construction of the first tide mill at Nendrum to AD 619—621 – some 20 years after the death of St Columba, the Irish missionary who took Christianity to Scotland and who founded the monastery on Iona, and a year before the founding of Islam in AD 622.

To read the complete article, please see CA 224 How the mill worked

How the mill worked

Sea water is stored in the millpond and is released through a narrow chute, called the penstock. The penstock has a downwards incline of about 15 degrees and narrows from top to base to act like a pressure hose. The mill itself is a two-storey structure that sits above the exit from the penstock and the lower storey houses a horizontal water wheel with spoon-shaped paddles.

The advantage of a horizontal wheel is that it needs no intervening gears to turn vertical into horizontal motion. The water that emerges at speed from the orifice of the penstock hits the paddles and turns the wheel, which is connected directly to the millstone by a simple vertical shaft.

The shaft passes through the ceiling of the wheelhouse to the floor of the millhouse, where it is attached to the upper stone of a pair of millstones. Grain fed from a hopper into the ‘eye’ of the upper stone is ground between the moving upper stone and the fixed lower stone.

The function of the bridge tree and lightening tree was to enable the gap between the upper and lower millstones to be varied: a wider gap was used to dehusk the grain and produce coarse meal, and a narrower gap was used to make finer meal and flour.