Norwich was the second largest city in Medieval Britain: why?

In recent years a number of major sites covering more than 20 acres in all have been excavated in medieval Norwich, which between them have revolutionised our knowledge of this crucial medieval city.

Let us take a look at these excavations in order to throw new light on this question of why medieval Norwich was so big, and so successful.

The origins of Norwich

Norwich was not a Roman settlement, nor does it owe its origins to the early Anglo-Saxon invaders. Settlement along the banks of the River Wensum began in the 8th and 9th centuries, and recent excavations in Coslany, to the north of the River, have discovered some of the earliest embankments of the river.

The Castle Mall

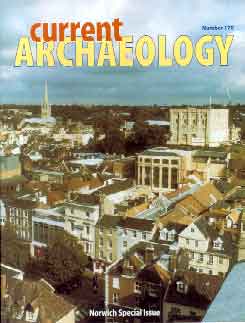

The Norman invasion was traumatic for Norwich. Nearly a quarter of the city was destroyed to make way for new buildings, most notably the huge castle, with the great Norman keep – seen here in the background – set upon a vast mound or motte. Here excavations are taking place in the side of the motte in order to insert a new lift for visitor access.

The biggest single excavation in Norwich has been of the Castle Mall. The Mall is the former bailey of the motte-and-bailey castle. This covered a huge area, but after the castle fell into disuse as a castle, the defences were flattened and it became the cattle market, and later a car park. It has now been made into a huge shopping centre, with three stories of car parking and then three stories of shops above. The extensive excavations revealed not only the castle defences, but also the remains of the Saxon town underneath.

The French Borough

The inhabitants of Norwich were a bolshie lot, and were not even cowed by the huge castle that the Normans plonked down in their midst. The Normans therefore decided to bring in some nice reliable French settlers who formed a new settlement, known as the French Borough, on the western side of the Saxon town. This has been little explored archaeologically, but in 1994 a disastrous fire destroyed the Norwich City Library, situated in the heart of the French Borough. But to the archaeologist, every disaster is an opportunity, and the fire was followed by an extensive ‘Millennium excavation’ which revealed the secrets of the French Borough.

One of the secrets was that there had been some earlier settlement – as this Viking gold ‘ingot’- here seen alongside a modern 20p coin – demonstrates

The Franciscan Friary

Like other medieval towns, Norwich was dominated by the monasteries. The friars came late, arriving only in 1226, but within 80 years they had already grown rich enough to construct a huge Friary on a site in the centre of the city, adjacent to the Castle, which can here be seen in the background. The excavations revealed not the church, but the cloisters and some of the buildings. Here the precinct wall can be seen running across the excavations – Friary to the right, town to the left.

The excavations also revealed a lot of information about the earlier Saxon town. Here we see left an early Saxon coin, a sceatta – and right a 14th century gilded silver brooch. Was it worn by a visitor to the monastery – or by a friar, in defiance of the oath of poverty?

King Street

Archaeology today is not just about rescue and research – it is also about regeneration.

King Street was once one of the great streets of Norwich, the main street to the south, running alongside the river, and thronged with rich merchant houses. One of these was Dragon Hall, recently restored; here we see the excavations taking place to the rear of the hall.

However the 19th and 20th centuries were not kind to King street, which has become run down: a great big brewery and storage depot was placed at its centre, over the remains of another of the great monasteries, the Austin Friars.But a regeneration policy is seeking to identify and preserve some of the older houses, and to restore the street to something of its former glories.

Paradise to come? Today commercial traffic has left the River Wensum, and it is increasingly used by leisure boats. The brewery storage depot on the right is awaiting demolition, but Dragon Hall, to the left, show what hopefully can be achieved.

This is based on a special issue of Current Archaeology – number 170, published in October 2000