‘Look after the soldiers’ was Roman emperor Severus’ advice to his successors. Officers were especially favoured, with centurions in the ancient equivalent of modern semis, and regimental COs in veritable mansions. With a new full-size reconstruction now open at South Shields, Nick Hodgson, Principal Keeper at Tyne and Wear Museums, describes a major project to bring to life the soldiers stationed on Rome’s wild north-west frontier in the 3rd century AD.

‘Look after the soldiers’ was Roman emperor Severus’ advice to his successors. Officers were especially favoured, with centurions in the ancient equivalent of modern semis, and regimental COs in veritable mansions. With a new full-size reconstruction now open at South Shields, Nick Hodgson, Principal Keeper at Tyne and Wear Museums, describes a major project to bring to life the soldiers stationed on Rome’s wild north-west frontier in the 3rd century AD.

What was a Roman centurion’s house like? Visitors to Arbeia Roman Fort at South Shields can now wander around a full-size reconstruction of one. The sheer size of it may come as a shock, as may the beds and couches, the kitchen area with built-in latrine, and the children’s toys. You could be inside a big modern semi-detached.

The plan of the house, and the rest of the attached barrack-block, which was reconstructed and opened to the public six years ago, is exactly the same as the excavated Roman original. The whole thing — as with all the reconstructions at South Shields — is on the site of the original building. South Shields lies on the north-east coast, at the mouth of the Tyne, not far from the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall. Here the Romans established a sea-port, and the fort is best known to archaeologists as a supply-base built around AD 210 and packed with 24 granaries capable of holding enough grain to feed 10,000 men for six months. The base, though built for the campaigns of Septimius Severus in Scotland, outlived both him and the failure of his northern adventure, showing that foodstuffs continued to be imported from far away to feed the soldiers stationed along Hadrian’s Wall.

South Shields lies on the north-east coast, at the mouth of the Tyne, not far from the eastern end of Hadrian’s Wall. Here the Romans established a sea-port, and the fort is best known to archaeologists as a supply-base built around AD 210 and packed with 24 granaries capable of holding enough grain to feed 10,000 men for six months. The base, though built for the campaigns of Septimius Severus in Scotland, outlived both him and the failure of his northern adventure, showing that foodstuffs continued to be imported from far away to feed the soldiers stationed along Hadrian’s Wall.

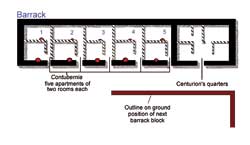

The barrack reconstruction depicts one of a series of half-a-dozen built inside the fort around AD 230 to house the Fifth Cohort of Gauls, the unit that guarded and administered the supply-base. It is the excavation of the whole set of barrack-blocks in detail over many years that has provided the main evidence for what the originals must have looked like.

We can be pretty sure about the form of the walls, because the lowest parts of the originals survived on the site. These were of rough facing-stones bonded using clay without mortar for the exterior walls, and wattle & daub for the internal partitions. Archaeologists tend to assume that clay-bonded stone walls never stood very high, being sills to carry a half-timbered superstructure. But excavation of the very barrack now reconstructed revealed a section of fallen masonry that proves that the external walls stood to full-height — two to three metres — in stone. The layout of the rooms (five contubernia, or two-room cells, each pair for eight men), and the centurion’s house at one end, was clearly revealed in the excavation. The daub walls inside had been destroyed in a fire and their lower parts survived, baked hard and red, in position. We know exactly how the doors were hung (the external ones on pivots, the internal with hinges) because pivot holes and iron door parts were found. Evidence from the site also confirms the use of whitewash inside and out, and red and white wall-painting in the centurion’s house.

The layout of the rooms (five contubernia, or two-room cells, each pair for eight men), and the centurion’s house at one end, was clearly revealed in the excavation. The daub walls inside had been destroyed in a fire and their lower parts survived, baked hard and red, in position. We know exactly how the doors were hung (the external ones on pivots, the internal with hinges) because pivot holes and iron door parts were found. Evidence from the site also confirms the use of whitewash inside and out, and red and white wall-painting in the centurion’s house.

Reconstructions become more conjectural once you move away from the ground plan. It is pretty certain that barracks in Roman forts were single storey: there are no signs of stairs. It is very likely, however, that the roof-space was accessible by removable ladder and used for storage, or even to accommodate slaves. So our reconstruction offers a view into the roof space. It has a roof covering of tiles, which we know were widely used in the fort in this period, though there is no direct evidence from excavation for the barrack-block itself, which could have been thatched or roofed in some other way.

The furnishings inside the rooms are also a problem, as excavation supplied little evidence for these. Alex Croom looked at what we know about furniture in this period, partly from remains found at other military sites (she found out enough to publish a book, Roman Furniture, available from Tempus). Unfortunately we still have no direct evidence from anywhere in the empire for how soldiers arranged themselves for sleeping in their barracks. The usual reconstructions showing bunk-beds are guesswork. So our reconstruction shows two alternatives in different rooms: one a communal bunk-bed, sleeping four up, four down; the other, eight separate couches.

The full article is published in Current Archaeology 215