Did 9th century Anglo-Saxon propaganda distort the records for the turbulent 5th and 6th centuries? Rather than Briton versus Anglo-Saxon — as in the myth of Arthur — was it simply a murderous struggle between rival British warlords? Archaeologist Miles Russell has been re-reading Dark Age history books.

Did 9th century Anglo-Saxon propaganda distort the records for the turbulent 5th and 6th centuries? Rather than Briton versus Anglo-Saxon — as in the myth of Arthur — was it simply a murderous struggle between rival British warlords? Archaeologist Miles Russell has been re-reading Dark Age history books.

Sixteen hundred years ago, in AD 409, the authorities in Britain rebelled against Rome, ejected the imperial officials, and set up their own government. What happened next is shrouded in Dark Age mystery.

For most people the ‘Dark Ages’ are just that: a period of time impenetrable behind a fog of myth, legend, and chronological uncertainty. Whilst academics theorise about the survival of Rome and the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons, popular culture revels in a fantastic world of warriors and sorcery. Period perception is fuelled by epic matter: dragons, giant-killers, Avalon, the sword in the stone, and the round table. Folk tales and legends coalesce around key mythical figures such as Arthur, Macsen Wledig, Coel, Merlin, Mordred, Ambrosius Aurelianus, Guinevere, and Morgana. The recent BBC series Merlin is, of course, the latest reworking of the myths.

Most of the characters that appear in the legendary accounts (The Matter of Britain) have been so extensively distorted by the passage of time that it is difficult to see where, when, or how particular tales began, and to whom they originally related. Macsen Wledig, appearing in the Welsh epic the Mabinogion, for instance, bears little resemblance to the Magnus Maximus of history, whilst Ambrosius Aurelianus, though cited in 6th century historical sources, appears in legend gathering stones from Ireland and re-erecting them to create Stonehenge.

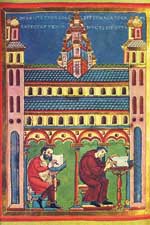

Perhaps the biggest problem for anyone attempting to make sense of the years following the collapse of Roman administration is the paucity of contemporary historical sources. Within the textual desert there are, of course, the writings of Dark Age stalwarts Gildas and Bede. Gildas’ world view, in his 6th century moral sermon De Excidio Britanniae (Concerning the Ruin of Britain), is one of anarchy and violence. Bede, the 8th century scholar, offers a more ‘English’ perspective in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People), but he makes much use of Gildas, paraphrasing him almost word for word in places.

Perhaps the biggest problem for anyone attempting to make sense of the years following the collapse of Roman administration is the paucity of contemporary historical sources. Within the textual desert there are, of course, the writings of Dark Age stalwarts Gildas and Bede. Gildas’ world view, in his 6th century moral sermon De Excidio Britanniae (Concerning the Ruin of Britain), is one of anarchy and violence. Bede, the 8th century scholar, offers a more ‘English’ perspective in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People), but he makes much use of Gildas, paraphrasing him almost word for word in places.

A more solidly ‘Saxon’ outlook is preserved in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, first compiled in the early AD 890s. Unfortunately, the Chronicle is a robust piece of historical revisionism, partially created in order to legitimise the English dynasty of Wessex, whilst also defining Saxon ethnicity in the face of 9th century Viking influence. The story it presents is full of unambiguous ethnic labels (‘Briton’, ‘Saxon’, and ‘Dane’); there is no blurring of ethnic, social, or political groups, as, in reality, there almost certainly was.

There are, of course, other sources. The Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), an epic work compiled by Geoffrey of Monmouth in around AD 1136, purports to chronicle the rulers of Britain from earliest times until the 7th century AD. The Historia contains much that is clearly fictional and, as a result, has often been ignored or derided. Geoffrey claimed that the inspiration for his work was ‘a very ancient [unnamed] book in the British tongue’; however, the absence of this book today has added weight to the view that he simply made it all up.

There are, of course, other sources. The Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), an epic work compiled by Geoffrey of Monmouth in around AD 1136, purports to chronicle the rulers of Britain from earliest times until the 7th century AD. The Historia contains much that is clearly fictional and, as a result, has often been ignored or derided. Geoffrey claimed that the inspiration for his work was ‘a very ancient [unnamed] book in the British tongue’; however, the absence of this book today has added weight to the view that he simply made it all up.

In addition to Geoffrey’s Historia there is the evidence provided by the Historia Brittonum (History of the Britons). This particular work is unfortunately not a single, coherent document, but a variety of disparate texts surviving in different locations and wildly differing forms. Identification of an ‘author’ in the conventional sense is almost impossible, although some forms have at times been ascribed to ‘Nennius’. A few of these versions may postdate Geoffrey’s Historia, although the majority were clearly set down a good few hundred years before, possibly as early as the 7th century AD.