Barry Cunliffe’s latest book represents the synthesis of half a century studying the archaeology of Europe, an achievement comparable with that of Gordon Childe in the 1930s. In this article, and in two more to follow in succeeding issues, Current Archaeology summarises his conclusions.

Barry Cunliffe’s latest book represents the synthesis of half a century studying the archaeology of Europe, an achievement comparable with that of Gordon Childe in the 1930s. In this article, and in two more to follow in succeeding issues, Current Archaeology summarises his conclusions.

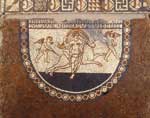

Europa was a Phoenician princess whose beauty captivated the Greek god Zeus. Disguising himself as a bull, Zeus joined a herd on the seashore, and, feigning gentleness, persuaded Europa to climb on his back. Thereupon he rushed into the sea and swam to Crete, where Europa later gave birth to his son Minos. The myth reminds us that ‘the seashore is a liminal place where unexpected things can happen’. It also highlights Europe’s intimate — perhaps even decisive — relationship with the sea.

Barry Cunliffe has spent 50 years studying the past through its archaeological remains. He has established a pre-eminent reputation for mastery of a huge corpus of Europe-wide data, and an ability to construct panoramic overviews of past epochs. His latest book is his most ambitious so far: nothing less than an attempt to synthesise 10,000 years of European history. His aim is to answer a question of huge world-historical significance: what made Europe special, such that it eventually grew to dominate the globe?

It’s the geography, stupid!

It’s the geography, stupid!

At first, the triumph of Europe can seem surprising. Geographically it is but ‘an excrescence of Asia’, and the first great civilisations were those based on the Nile, the Tigris/Euphrates, the Indus, and the Yellow rivers. By comparison, Early Europe can appear peripheral and backward.

Yet Europe is uniquely blessed by its distinctive geography. Its long and deeply indented coastline is 23,000 miles long — equal to the circumference of the Earth — and it is bounded by great seaways: the Baltic, the North Sea, the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea. No European is ever far from the sea; as Socrates put it, Europeans cluster like ‘ants or frogs around a pond’. Equally, Europe’s rivers are numerous, long, and highly navigable. The Volga, the Dnieper, the Vistula, the Oder, the Elbe, the Rhine, the Seine, the Loire, the Garonne, the Ebro, the Po, the Danube: these and others have been Europe’s great thoroughfares for thousands of years.

Though dissected by mountain ranges, there are ways through. The Middle European Corridor runs from the steppes of South Russia, through the Danube’s Iron Gates, across the Hungarian Plain, and on into Western Europe. The North European Plain is an open expanse extending from the Paris Basin to Moscow. Both have been routeways of mass movement across Europe from the Neolithic to the Nazis. North-south movement is harder, but the rivers help, and the mountains are crossed by numerous passes. None of the ranges constitutes an impenetrable barrier.

This topography harbours a greater variety of eco-zones than in any other area of comparable size on Earth. The Gulf Stream, originating in the tropics and sweeping around the western, northern, and eastern fringes of the Atlantic, moderates the European climate and shapes a series of distinct zones — the frozen tundra of the far north, the cold forests of the taiga belt of Northern Russia and Scandinavia, the wide temperate zone of mixed-oak woodland in Western Europe, the open steppe-land of Central and Eastern Europe, the warm Mediterranean littoral hemmed in between mountain and sea in the far south.

The effect, argues Cunliffe, is decisive for the development of economy, society, and culture. Historians of the French Annales school have taught us to distinguish between events, ‘conjunctures’, and the longue durée. The Battle of Britain was an event. The Second World War — along with the events leading up to it, and the consequences flowing from it — represents a conjuncture. But, it is the development of global capitalism from the late 18th century to the present that is decisive in framing and shaping contemporary human experience: this is the longue durée. And it is this which, argues Cunliffe, ‘is geographical time — a time of landscapes that enable and constrain, of stable and slow developing technologies and of deep-seated ideologies.’

To read the full article, see CA 229